A Note for Al Rio/To the River

This text was featured in The Against Nature Journal (T.A.N.J.) issue #2, published by Council in 2021, as an introduction to Zoe Leonard’s artistic contribution with photographs from the series Al Rio/To the River.

A river boundary naturalizes a nation’s edge. But forcing rivers to perform the role of international boundary proves very difficult without tremendous, even violent, effort to control the river’s behavior. A river, especially a desert river, is essential to the life that surrounds it. In this way, rivers function more like centers than edges, providing sites of hydration and gathering for all the species that rely upon them. Moreover, rivers meander; they flood and jump their banks. Rivers make new, sometimes multiple, courses. In time, the land which shapes rivers is shaped by them. River behavior troubles boundaries and disrupts property, often dramatically. One con- sequence of river boundaries is a profound anxiety at the very site of a nation’s (or any other entity’s) edge. Attempts to control rivers, and to control their related phenomena, though effective in some ways, are rarely effective for long. For the most part, this failure of architecture and other modes of intervention to control rivers has resulted in greater and more violent forms of intervention. And that doesn’t begin to address the impacts, both intentional and unintentional, which these interventions introduce.

The photographs in this issue of T.A.N.J. are excerpted from Al Rio/To the River, a large-scale photographic work in progress by Zoe Leonard. A book of the same name, a collaboration with the artist which I am editing, will accompany the work when it appears in 2021. 1 2

Since late 2016, Leonard has photographed from both banks of the Rio Grande/Río Bravo, following the course of the river where it is used to demarcate the international boundary between Mexico and the United States. In Al Rio/To the River, as in much of her work, Leonard uses strategies of seriality and shifting perspective to investigate the myriad ways in which the politics of depiction and representation coincide with lived experiences of sexuality, gender, mourning, migration, and displacement.

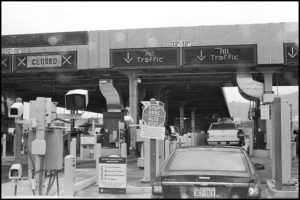

Across several hundred photographs, Al Rio/To the River engages a sustained observation of the water, the surrounding landscape, and the constructed environment—dams, levees, roads, irrigation trenches, bridges, pipelines, fences, checkpoints, and detention centers—built into and alongside the riverbed to control the flow of water, the passage of goods, and the movement of people.

Much of the Río Bravo/Rio Grande flows through the Chihuahuan Desert, which encompasses several states and parts of both nations. The breadth of the river’s mouth as it reaches the Gulf of Mexico results in most of what isn’t desert. The significance of rivers to the region is evident in the name Chihuahua, which derives from the Nahuatl (the language of the Aztecs) word for “confluence,” a reference to where two rivers, the northerly Conchos and southerly Bravo/Grande, meet. Today the confluence is known as La Junta de los Ríos, the name used by the earliest Spanish conquistadors.

For several thousand years, humans have lived at La Junta. During that same time, the people who have arrived at La Junta on their way to more distant points vastly outnumber the people who have forever called it home. Today we would call it a cross- roads, but anachronistically. In fact, it is rivers that have provided us with the ancestral routes of movement and association that later roads have followed. Today, La Junta de los Ríos is located about three kilometers west of the International Bridge connecting Ojinaga, Chihuahua, and Presidio, Texas.

The photographs in this selection were taken at locations along nearly 2,000 kilometers of river boundary and include: the former site of the Candelaria Bridge, which, until its removal by US Border Patrol in 2008, connected the remote villages of Candelaria, Texas, and San Antonio del Bravo, Chihuahua; the Los Ebanos Ferry, also known as El Chalán, the hand-operated cable ferry that connects the towns of Los Ebanos, Texas, and Gustavo Díaz Ordaz, Tamaulipas; bridges connecting Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, and El Paso, Texas; and a bridge connecting Laredo, Texas, with Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas.

Zoe Leonard is an artist working with photography, sculpture, and installation. She has exhibited widely since the early 1990s, with recent solo exhibitions at MOCA—Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (2018), Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (2018), and MoMA, New York (2015). Her project Al Rio/ To the River will be shown at Mudam, Luxembourg, and MAM Paris.

Tim Johnson is a poet and artist based in Marfa, Texas. With his partner Caitlin Murray, he operates Marfa Book Co., a bookstore, gallery, and publishing company. He is also the cohost of a weekly Spanish language radio program on Marfa Public Radio, Dos Horas Con Primo.

TEXT BY

Tim Johnson

ARTISTIC CONTRIBUTION

Zoe Leonard

This text was featured in The Against Nature Journal (T.A.N.J.) issue #2, published by Council in 2021.

SUPPORT FOR THE ARTWORK GIVEN BY

the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts

the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation

Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne

Hauser & Wirth, New York

Top image : T.A.N.J #2, 2020, Council. Ph. by Stepan Lipatov.

T.A.N.J. #2

Articles

Rethinking Migration

— Aimar Arriola & Grégory Castéra

A Note for Al Rio/To the River

— Tim Johnson